This coverage is made possible through a partnership between WABE and Grist, a nonprofit environmental media organization.

At low tide on Tybee Island, the beach stretches out wide as small waves break far away across the sand — you’ll have a long walk if you want to take a dip. But these conditions are perfect for a team of researchers from the University of Georgia’s Skidaway Institute of Oceanography.

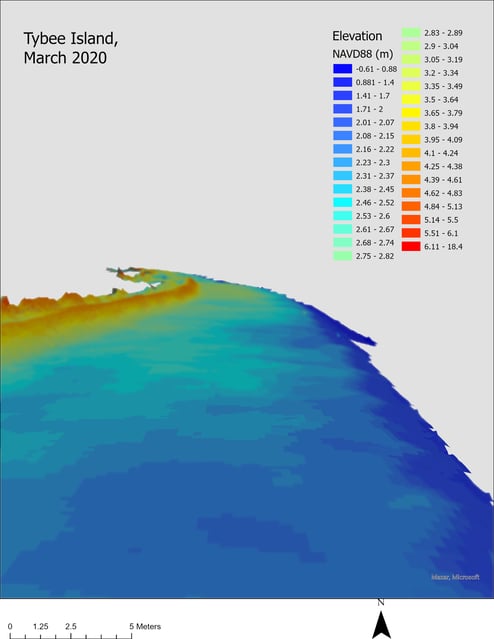

Every three months, at low tide, they set out a miniature helipad near the foot of a dune and send up their drone equipped with LiDAR — technology that points a laser down at the sand and uses it to measure the elevation of the beach and dunes. The team flies the drone back and forth from the breakers to the far side of the dunes and back until they have a complete, detailed map of the island’s seven-mile beach, about 400 acres.

“It’s high accuracy, it’s a high resolution,” explained research technician Claudia Venherm, who leads this project. “I see every flip-flop on the beach.”

That detailed information is crucial because Tybee is a barrier island, and rising seas are constantly eating away at the sandy beach and dunes that protect the island’s homes and businesses as well as a stretch of the Georgia mainland.

Homes on this low-lying island have been swamped by hurricanes over the past decade. As climate change drives sea levels higher and threatens more extreme storms, maintaining the protection offered by the beach and the dunes only gets more important.

Knowing exactly where the island is eroding and how the dunes are holding up to constant battering can help local leaders protect this piece of coastline.

“Tybee wants to retain its beach. It also wants to maintain, obviously, its dune. It’s a protection for them,” said Venherm. “We also give some of our data to the Corps of Engineers so they know what’s going on and when they have to renourish the beach.”

Since the 1970s, the Army Corps of Engineers has helped maintain Tybee Island’s beaches with regular renourishment: Every seven years or so, the Corps dredges up sand from the ocean floor and deposits it on the beach to replace sand that’s washed away. The data from the Skidaway team will help the Corps do this work more effectively. LiDAR isn’t new, and neither is aerial coastal mapping. Several federal agencies monitor coastlines with LiDAR, but those surveys are more typically several years apart for any one location, rather than a few months.

The last renourishment finished in January 2020, and Venherm and her team got to work a few months later. That means they have five years of high-resolution beach data, recorded every three months and after major storms like Hurricane Helene, creating a precise picture of how the beach is changing.

“I can compute what the elevation of the dune is, as well as how much volume has been lost or gained since a previous survey,” said Venherm. “I can also compute how long it will take until the beach is completely gone, or how long will it take until water reaches the dune system.”

The Corps conducts regular renourishment projects on beaches all along the East Coast, and uses a template to inform that work, said Alan Robertson, a consultant who leads the city of Tybee’s resilience planning. But he hopes that such granular evidence of specific changes over time can shift where exactly the sand gets placed within the bounds of that template. An area near the island’s north end, for instance, is a clear hotspot for erosion, so the city may push for concentrating sand there, and north of that point, so that it can travel south to fill in the eroded areas.

“We know exactly where the hotspots of erosion are. We know where there’s accretion,” he said, referring to areas where sand tends to build up. “[We] never had that before.”

The data can also inform the city’s own decision making, because it provides a much clearer picture of what happens to the dunes and beach over time after the fresh sand is added. In the past, they’ve been able to see the most obvious erosion, but now they can compare how different methods of dune-building and even sources of sand hold up. The vegetation that’s critical to holding dunes together, for instance, takes root far better in sand dredged from the ocean compared to sand trucked in from the mainland, Robertson said.

“There’s an example of the research and the monitoring. I actually can make that statement,” he said. “I actually know where you should get your sand from if you can, and why. No one could have told you that eight years ago.”

That sort of proven information is key in resilience projects, which are often expensive and funded by grants from agencies that want confirmation their money is being spent well.

“Everything we do now on resiliency, measuring and monitoring has become a priority,” said Robertson. “We’ve been able over these years through proof statements of ‘look at what this does for you’ to make it part of the project.”

This story is available through a news partnership with WABE, Atlanta’s National Public Radio affiliate, and Grist..

You must be logged in to post a comment.